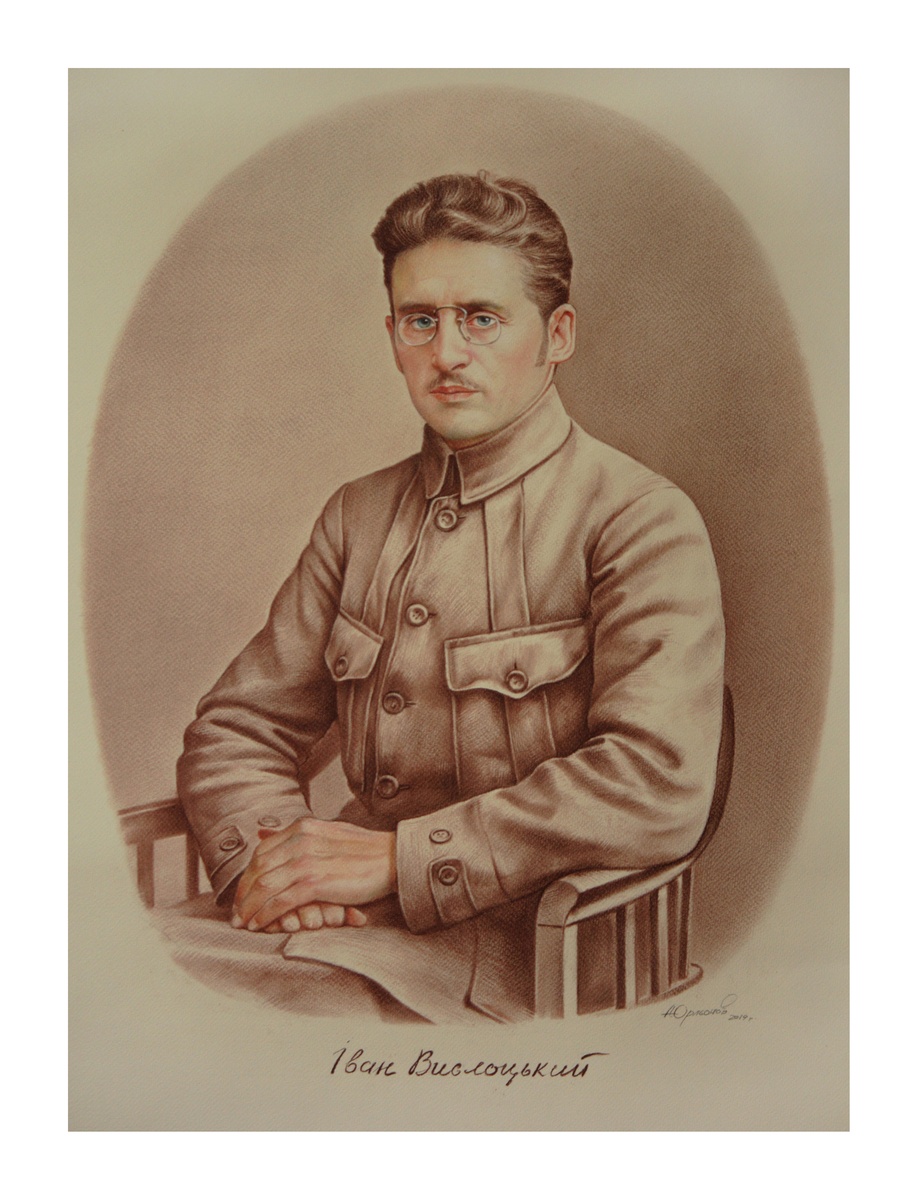

July 24, 1893 – Ivan Vyslotskyi – Mykhaylo Hrushevskyi's Bodyguard and an Intelligence Officer of the Ukrainian Galician Army – Was Born

7/23/2020

Ivan, the son of a priest from the Lemko region, which was then part of Austria-Hungary, had never imagined such a fate. As an 18-year-old volunteer, he joined the Austrian army, graduated from the intelligence school in Bregenz, and then performed some tasks at the headquarters of the corps based in Przemyśl. During the First World War he was taken prisoner by the Russians and taken to Chita. And now he was in Ufa.

The first reports on the revolution evoked joyful feelings and suggested that the Russian Empire was beginning to collapse, to lose ground, and that he would live to see a better fate. The captured Galicians, of whom there were about two dozen, stuck together and hung on news from Ukraine. From one of the newspapers they learnt about the first Ukrainian military congresses in Kyiv, about attempts to create Ukrainian regiments in the Russian army. Later they learnt that there, in Ufa, in the 189th Infantry Regiment, a Ukrainian Kurin (Regiment) was created under the command of Lieutenant Barabash.

And when the first soldiers with yellow and blue colors on their hats appeared in the streets of Ufa, it was a real holiday for Ivan. The group of Galicians, which he belonged to, instructed him to get acquainted with Barabash. The Lieutenant greeted the captured Galicians warmly. They learnt from him that there was already a Ukrainian Committee in Ufa, which took care of numerous refugees and deportees from Galicia.

– We want to join the Ukrainian army, – Vyslotskyi declared at the next meeting.

– How do you imagine it? – the Lieutenant asked.

– Let's change into Russian uniforms, wear Ukrainian insignia, like the soldiers of your Kurin, and go to Ukraine together.

After a difficult travel with many adventures, in early March 1918 they arrived in Kyiv.

Passers-by showed them the way to the Pedagogical Museum, which housed the Central Rada. There they learnt from the guards that they had to go to Lvivska Street to the barracks of the Sich Riflemen. Dozens of fugitives from the front and Russian captivity arrived there every day.

Those who joined the Sich Rifle Regiment had to begin as ordinary riflemen. But in a few days Ivan became a platoon commander, and later a warrant officer. In this capacity he had to command the guard in the building of the Central Rada several times. There seemed to be no greater happiness and joy than being a Ukrainian soldier and guarding the Ukrainian government.

But the euphoria did not last long. In April, the Central Rada was defeated and replaced by the Hetmanate. German troops entered Kyiv and from the first days began to take control of all key facilities.

On one of those days in the afternoon, Colonel Yevhen Konovalets convened a meeting of officers and the Riflemen's Council. Vyslotskyi was also present at the meeting. He listened sadly to the words of the head of the Sich Rifle Regiment that the former leaders of the Central Rada were in danger. Everyone was ordered not to leave the barracks, to receive ammunition and to increase vigilance.

On the same day, Ivan and a platoon of the best soldiers were sent to Tereshchenkivska Street to guard Mykhailo Hrushevskyi. There he eye-witnessed an attack on the Head of the Central Rada. One of the soldiers attacked Hrushevskyi and wanted to stick him with a bayonet, but several officers and riflemen prevented the murder.

The next day, at the barrels of German machine guns and cannons, the Sich riflemen laid down their weapons. Some objected and shouted that it was a shame to just surrender without a fight, but obeyed the order. In desperation, some shooters broke their rifles so that the weapon would not fall into the wrong hands.

Soon Captain Vasyl Kuchabskyi called Ivan Vyslotskyi and three senior officers and ordered:

– Here's an address. Go there immediately, Mykhailo Hrushevskyi is hiding there. Until everything is settled, you must guard him day and night.

In memory of this important task, throughout all his life Vyslotskyi kept Hrushevskyi's photograph, given to him by the Professor with a dedicatory inscription.

The Sich Rifle Regiment was soon reformed. Some volunteered to remain in the service of Hetman Skoropadskyi, others did not accept the new government and went to the village to weather the storm. Ivan Vyslotskyi was among them.

After the establishment of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic in the autumn of 1918, the formation of a regular Ukrainian Galician Army to defend its statehood began immediately. An important place in its structure was given to the Intelligence Department, which was structurally subordinated to the Supreme Command – the highest governing body of the Ukrainian Galician Army.

The initiator of the establishment of the intelligence service in the Galician troops became the Commander of the UGA Colonel Dmytro Vitovskyi. The Chief of the Intelligence Department in early 1919 was appointed Lieutenant Rodion Kovalskyi.

The Department included units that conducted both intelligence and counterintelligence. And the personnel began to be called detectives.

One of the detectives who had been acquainted with Vyslotskyi since their service in the Austrian army, once in the spring of 1919 happened to meet him on the street.

– Wouldn't you like to serve in the intelligence again? – he asked.

– Why not.

Having received Vyslotskyi’s prior consent, he introduced him to the Chief of the Department Kovalskyi. A short conversation about the previous service made quite a positive impression and Vyslotskyi becomes a senior officer of the Intelligence Department.

This Department was the leader of the entire intelligence service – wrote in his memoirs Ivan Vyslotskyi – and was originally called Vyvidchyi Department, abbreviated VV, and later, until the end of its existence, the Department was called Rozvidchyi (Intelligence) Department or RV. It included senior intelligence officers of brigade commands and of district support commands in Halychyna, as well as senior officers who were at some important places on both sides of the then Ukrainian-Polish front and the border with Romanians. Besides, there were units of field intelligence, reconnaissance aviation, “propaganda” department, which organized information-propaganda activities.

Despite such an established intelligence structure, there was a lack of good specialists in the staff. Ivan noticed this immediately. He got some intelligence training in the Austrian army and could compare. Of all the intelligence officers in the department, who numbered up to thirty, only five or six were professionals. The rest were beginners.

Those who had served in the Austrian intelligence did not want to serve in the Ukrainian one. They explained their refusal not only by a small salary. They complained that members of the government and senior military officials in the Ukrainian army did not understand what the intelligence was about and why it was needed. Because of this, even professional officers with intelligence experience refused to serve in the intelligence and went to the army to command companies or regiments.

Nevertheless, the efforts of Lieutenant Rodion Kovalskyi and patriots such as Ivan Vyslotskyi succeeded in changing attitudes to the intelligence. At that time, the work of the intelligence by stages of activity was divided into two main periods: Galician, during which there was the war with Poland, and the Dnieper, when there were hostilities with the Red and Volunteer armies. UGA’s intelligence agents also collected information about their allies, the UPR's Active Army, because there were good reasons for this.

Once, when both the brigade and corps intelligence officers were killed by typhus, a telegraphic message came from the army headquarters to urgently send Vyslotskyi to carry out some assignment. And although he himself had just returned from another task and was unwell, he still had to go. Having reached the location of the brigade, he learned from the commander the essence of his task.

– From the north, Bolsheviks are taking their troops by train to Zhytomyr region, where their army is gathering to attack our positions, – he began. – This must be prevented, or at least restrained for a longer time, so that we have the opportunity to retreat to the south.

– How best to do it? – Vyslotskyi asked.

– It is necessary to blow up the railway bridge south of Korosten. And to do so when the Bolshevik train passes through it, so that the damaged tracks and cars cause the Bolsheviks the most trouble during the repairs.

– But I know nothing about the sappers' work, – said Ivan.

– Don't worry, we'll give you good sappers.

Before leaving, Vyslotskyi talked to the sappers, made sure they were professionals, and took with him a former railway official with a telephone and a guide-sergeant who knew the area. They mounted the horses and, wasting no time, set off in fresh snow. The bridge was about 80 kilometers away, so they had to hurry.

They crossed the front line unnoticed. In the morning they found themselves 30–40 kilometers into the enemy's rear. They had some rest on a deserted farm and moved on.

A kilometer from the bridge they noticed a railway guard's booth. Within minutes, they quickly and without a single shot captured the guards. In another 15–20 minutes, everything was ready for blowing up: the explosive was attached to the bridge piers so as to cause the greatest damage. They jumped on horse backs and retreated to a safe distance. They waited for several hours. Early in the morning a buzzing sound was heard from afar.

The train was approaching a bridge over a small river between two hills. The railway was descending slightly to the bridge. All this was an advantage. Suddenly something on the bridge flashed in a large semicircle under the train, and there was a terrible roar. The bridge seemed to squat under the weight of the train. The cars were falling down along with metal structures. Others were piling on top. Time and time again there were explosions of ammunition. Not a single car remained on the bridge – everything had fallen down.

Less than 10 minutes later, the whistle of a new locomotive going on the bridge sounded. Guns could be seen on open platforms. The driver gave an alarm and began to brake. But it was too late. The steamer slid into the river, followed by cars. There was a loud explosion. Probably of a boiler with steam. Then artillery shells began to explode.

The next task was no less risky. Ivan had to bypass the enemy's southern flank, go to the rear and find out what maneuvers the retreating enemy was resorting to, and most importantly, to find out if the Reds had tanks there.

He spent two weeks in a hostile environment, and eventually collected the necessary information. “There are tanks,” he reported after his return, “but the Reds sent them against the Volunteer Army”. For the fulfillment of this task, he was promoted to a platoon commander.

One of the significant achievements of the Intelligence Department at that time was the arrest in Vinnytsya of the Chief of Polish Intelligence Poruchnyk (Lieutenant) Kowalewski who provided them with very valuable information concerning the actions of the Polish Army on the Eastern Front.

However, it should be acknowledged that although the UGA's intelligence was successful, it could not be compared to the Polish, Soviet or Denikin's ones due to the lack of qualified professionals, funds and insufficient attention of the military leadership to this important matter. In addition, the intelligence work of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic in the occupied territory of Halychyna was complicated by the Polish secret services' strict counterintelligence control.

Eventually, the forced merger of the UGA with the Red Army led to the elimination of the intelligence of the Galician army. The Bolsheviks first tried to take the intelligence officers into their hands and shot them without trial or investigation. In the spring of 1920, the UGA and its special services virtually ceased regular activities. At the same time, most army officers and riflemen, intelligence and counterintelligence officers went underground, joined insurgents and national liberation movements.

Similar fate befell Ivan Vyslotskyi. With his young wife Nadia Oleksiyiv, with false passports he managed (with adventures) through Odesa, Varna and Belgrade to arrive in Vienna. Then he moved to the Trans-Carpathian Ukraine, which at that time was part of the Czechoslovak Republic. In 1936–1939 he worked in Lviv Publisher House. Before the arrival of the Red Army in September 1939 he and his family got to his native Lemko land, and in autumn 1941 he settled in Sambir, where he was publishing new school textbooks without communist stereotypes. In 1944, his family and he found themselves in the camp for displaced persons in Germany, from where in 1948 he left for Paraguay. Overseas in his later years he taught children of immigrants to read and write Ukrainian. He died in 1969 in Argentina.